François Larderel, a young Frenchman having come to Tuscany in the early 19th century, discovers a hidden treasure: Boric Acid. He devotes his life to design a method to extract this mineral from the vapours of the earth and then builds a small industrial empire around the production of Boron products.

His descendants developed the business to a higher scale and turned it, in the early 20th Century, into a renewable energy industry that still thrives today in a region close to the beautiful cities of Volterra and Massa Marittima.

When in 1814, at the age of twenty-five, François Larderel landed in Livorno from his hometown of Vienne (in the Dauphiné in France), his intention was to take advantage of the situation created fifteen years before by Napoleon's occupation of Italy to live an adventure. Others left for the Americas, but François was attracted by the many possibilities that in those early decades of the nineteenth century, Tuscany and the area of Livorno offered to enterprising people thanks to the intellectual, commercial and financial very active local life, led by many talented people including many French and other foreigners.

We do not know what wanderings brought the young Francesco to the Metalliferous Hills (colline Metallifere), in the area between Volterra and Massa Marittima, but it is certain that his training as a chemist, supported by previous research conducted by Francesco Hoefer a scientific, director of the pharmacies of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany ruled by the Lorraine family, soon enabled him to biancane_articolorecognize between “moffette” (by analogy with the skunk’s ill smell) and 'putizze' (area devoid of vegetation due to the high temperature of the subsoil and the existence of small geysers, the “soffioni”) the presence of Borax, a valued chemical product at that time, mainly used as a disinfectant. The area of the discovery was close to Montecerboli (Mount of the Devil in Latin and a good name if you consider odors, heat, and smoke!), A stone's throw from the Bagno al Morbo, which was in turn included in the broader area identified at the 3rd century AD by the Romans in the Tabula Itineraria Peutingeriana, where there were the hot springs 'Volaternas'.

Identifying the presence of the desired chemical was a step forward, but extracting it and then marketing it was a different story! The first company, whose aim was the extraction of borax, was founded in 1817 by Francesco (not anymore François!) Larderel along with two other compatriots, the extraction method was very primitive: the water in the lagoons was placed in large pools heated by wood fires, the evaporation of water allowed the crystallization of borax, which was then collected, refined and sold. But the fuel was expensive and the sourcing of wood more and more difficult and burdened by increasing transportation costs. The extracted borax could not, therefore, have the sufficient margin to maintain a healthy development of the company. Less than ten years after its creation, this first industrial experience ended and the company was dissolved.

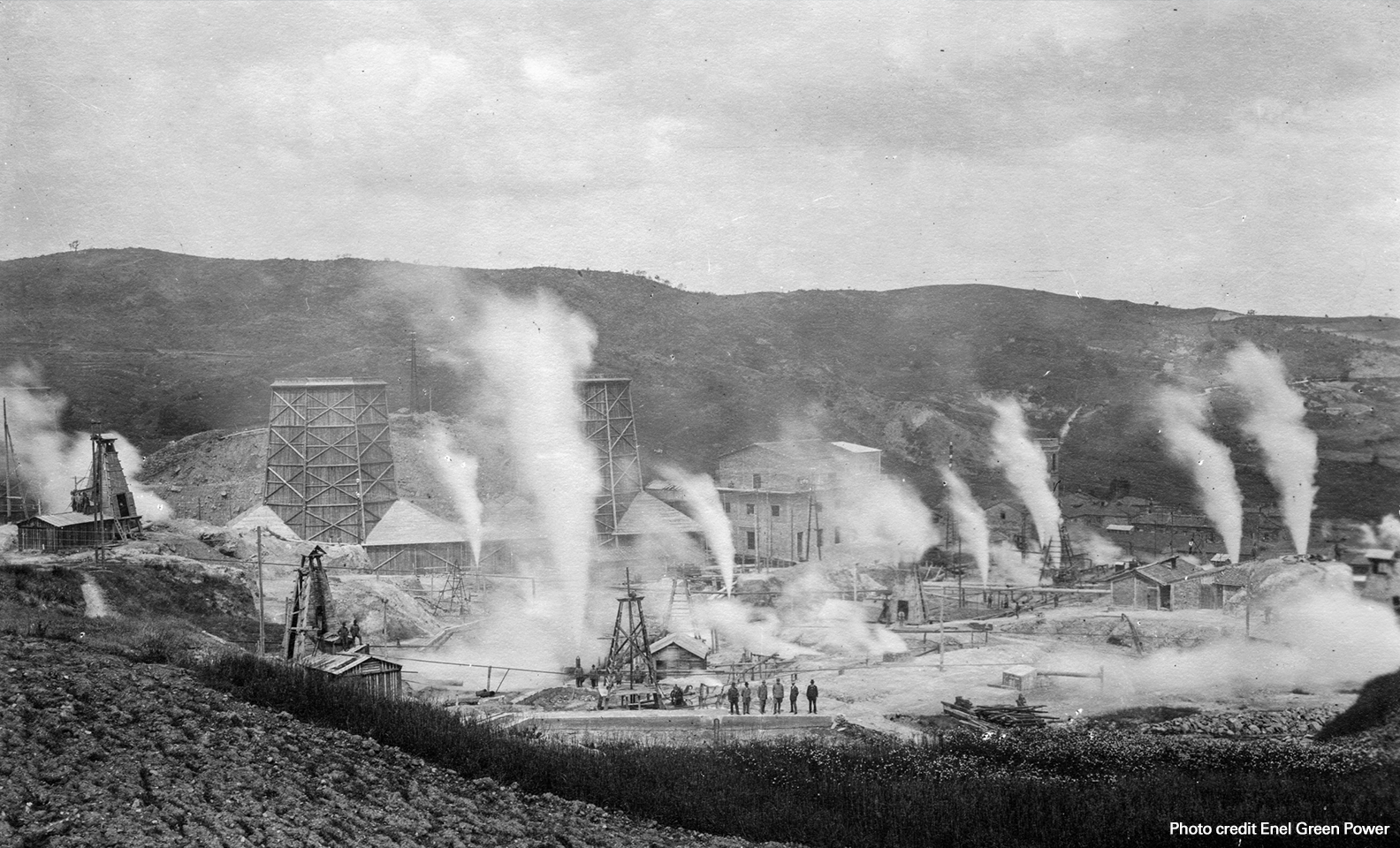

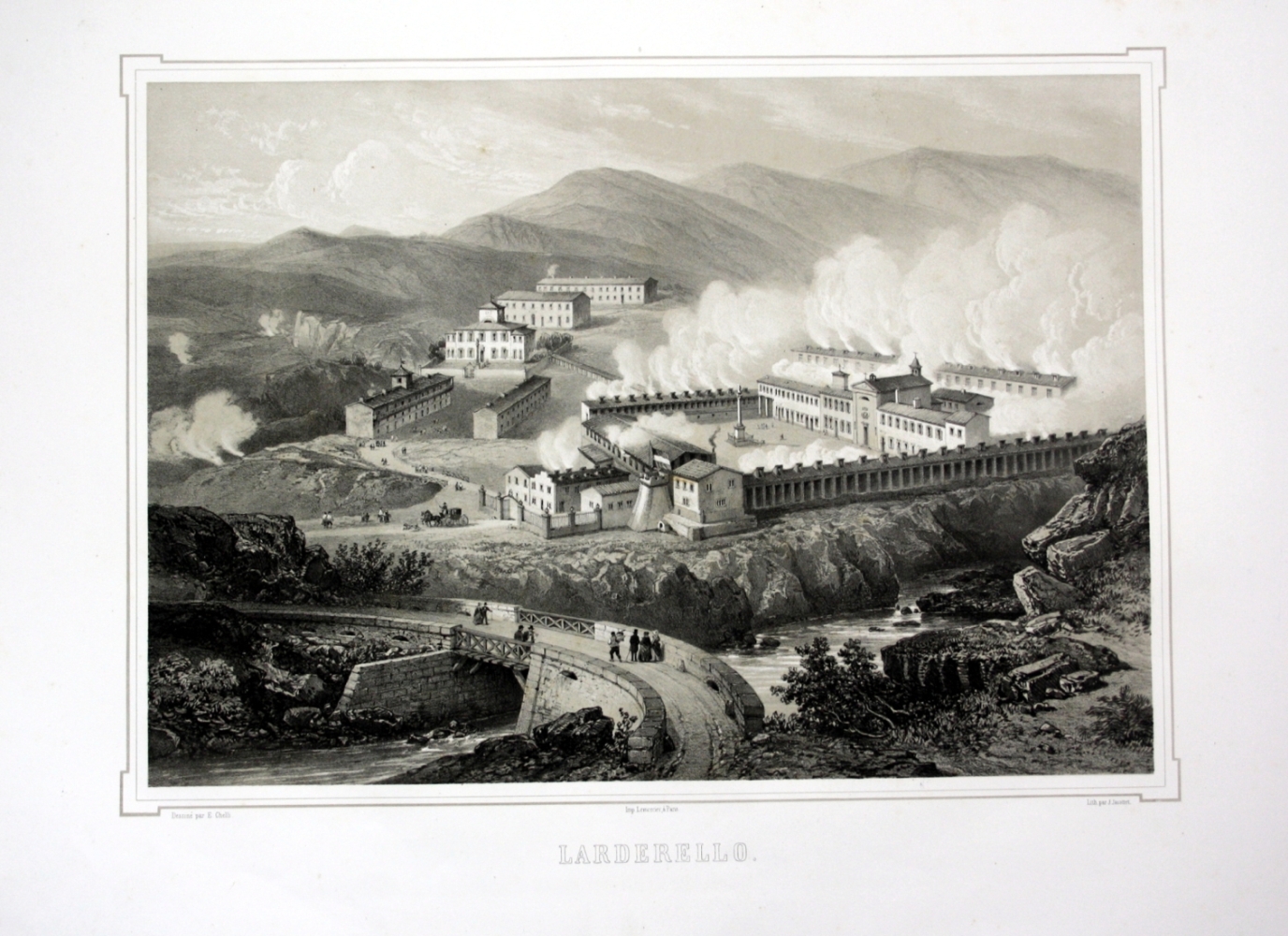

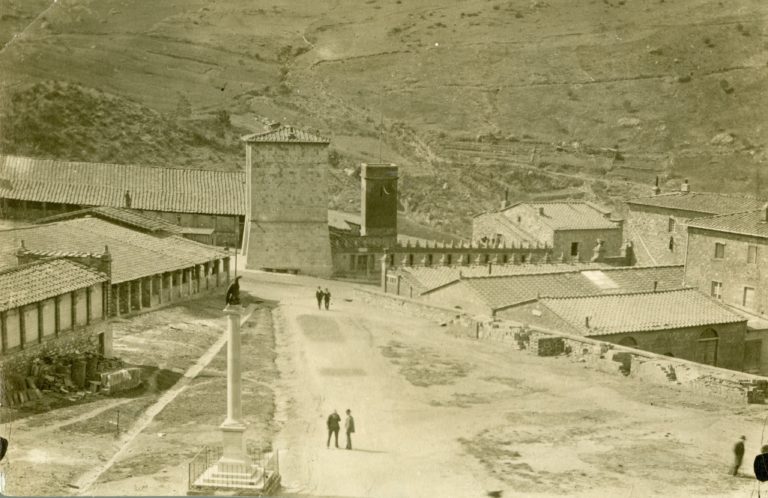

Francesco Larderel had a brilliant idea: why, instead of firewood, do not use the same heat that came freely from underground at high temperatures in order to evaporate the water contained in the pools and so crystallize borax at a small cost? This time, the road was clear to boost the activity on new premises. In 1826 Francesco Larderel created a new company - this time in his name only - that with high yields, low production costs and high quality year after year progresses contributing not only to the personal enrichment of the Larderel family, but also to that of Tuscany. In a relatively short time, around the main factory which the Granduca of Tuscany Leopold II, in recognition of the work carried out by Francesco Larderel named Larderello, new factories of smaller size were born in Castelnuovo di Val di Cecina, Sasso Pisano, Serrazzano, Lustignano, Lago Boracifero and Monterotondo.

Many would have been content with this state of affairs: A valued product, a performing company, sure profits. Francesco Larderel, however, dealt not only with the 'what' but also the 'how': Having been exposed to the ideas of the French Revolution, perhaps because of an innate humanist belief, perhaps in order to attract competent manpower in areas at that time isolated and inhospitable and prey to malaria, he wanted to definitely improve the standard of living of those who were part of his industry: As the company became more prosperous, the industrial site is started to get a school, a doctor, a pharmacy, a general store, a church, a system of social assistance to people in need in the area, not forgetting the fun with a municipal band to accompany the dances of the time. The whole organization was run according to Internal Rules' drawn up by Francesco Larderel himself that spelled out clearly in writing the duties of each member of his company.

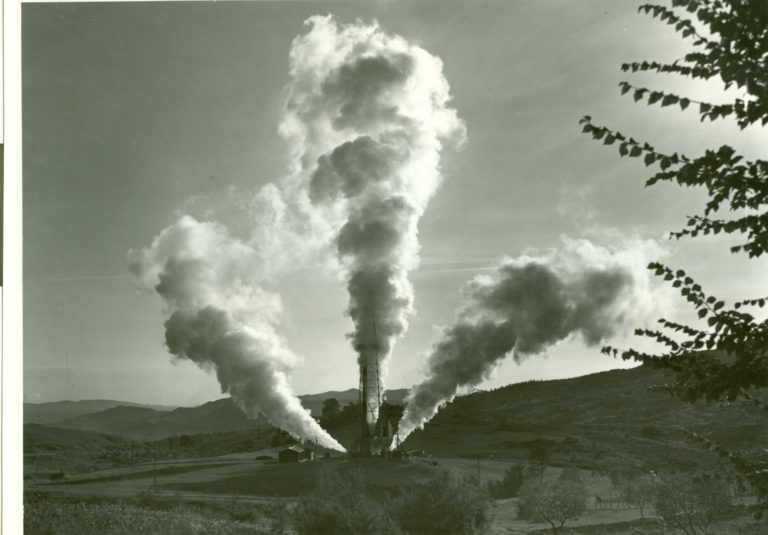

Old age, then the disappearance of Francesco Larderel did not prevent the company from progressing further, under the direction of three successive generations of Larderel’s, innovating technically with further improvement of productivity and processes for refining Boric Acid (Adriana boiler), deeper under the ground research for steam (manual drilling gradually replaced by drills driven by steam), steam pumps and then, in the early twentieth century, production of alternative energy, using alternators coupled to steam turbines powered by the same endogenous vapors to produce electricity (an idea of a member of the family, Prince Piero Ginori Conti).

The activity of Francesco Larderel received well-deserved riches and honors he shared with the many people who seconded him. One of the nicest rewards received, however, is contained in the Larderel family motto: 'Honor summum Industriae munus' (the reward from work is the highest honor!).

The nationalization by the Italian state of Larderello SPA and its integration into today's ENEL allow for the continuation of Francesco Larderel’s great adventure, permitting a large part of Tuscany to receive electricity through renewable energy. Today, a visit to the Larderel museum in Larderello http://geomuseo.enel.com/ explains clearly the technological history begun by Francesco Larderel and makes one discover a beautiful area of Tuscany, surrounded by gems such as Volterra and Massa Marittima.

Vecchienna is an extraordinary example of a nineteenth-century model farm (“fattoria”) established by the French engineer and industrialist François de Larderel, set in the rolling hills of Upper Maremma in Tuscany. Built in the mid-1800s, the complex was designed not merely as a farm, but as a self-sufficient rural village — with carefully laid-out agricultural buildings, residential quarters, communal facilities and production units. Today it stands as a historic monument (a member of the Associazione delle Dimore Storiche Italiane) that bears witness to both industrial ambition and pastoral life.

At the heart of Vecchienna lies the Villa, the grand residence which anchors the estate. Surrounding it are essential production buildings — the cantina (wine cellar), the frantoio (olive oil mill), and the segheria (sawmill) — that once processed the estate’s own grapes, olives, timber and other resources. Also included were buildings for carpentry, barns, and utilitarian workshops, each clearly marked with its function. The estate also contained a school, wash-house, and housing for workers, reflecting Larderel’s vision of a community in which both work and welfare could be integrated.

Vecchienna’s agricultural activity was diverse: cereals, olive oil, vine cultivation and cattle breeding (today notably Limousine cattle) were among its economic pillars. Over time rural depopulation affected many of the smaller “poderi” (farm estates) and traditional farmhouses scattered across the land, but the core infrastructure retains its original layout and many of its structures. The Podere San Giuseppe, for example, has been restored and adapted as holiday properties, demonstrating how the historic farm economy and tourism can coexist.

Beyond its buildings and agricultural production, Vecchienna offers a striking location: perched on a hill, surrounded by Mediterranean forests, and only about thirty to forty-five minutes from the sea. The landscapes, the horizon (even views toward the Isle of Elba) and the sunset light imbue the estate with a special beauty. Today Vecchienna is both a living farm and a heritage site, embracing sustainable agriculture (e.g. organic Limousine cattle, olive oil) alongside hospitality, renovation of historic structures, and preservation of its architectural and cultural identity.